The ancient mosaics found in floor paving throughout Israel and the West bank exemplify an art form practiced through centuries of invasions.

Pina Lomb delves into the ancient mosaics of ancient Israel, exploring how these intricate works, steeped in Greco-Roman, Jewish, and Christian traditions, reflect a cultural tapestry that has shaped the region’s unique artistic heritage.

ISRAEL—The ancient mosaics found in floor paving throughout Israel and the West bank – when separated on their own, as is their nature, grouped along state boundaries created in contemporary times, exemplify an art form practiced for centuries throughout Mesopatamia, the Roman and Byzantine empires. The fact that a culture and a language was maintained throughout each subsequent invasion causes one to look carefully at the characteristics of this region.

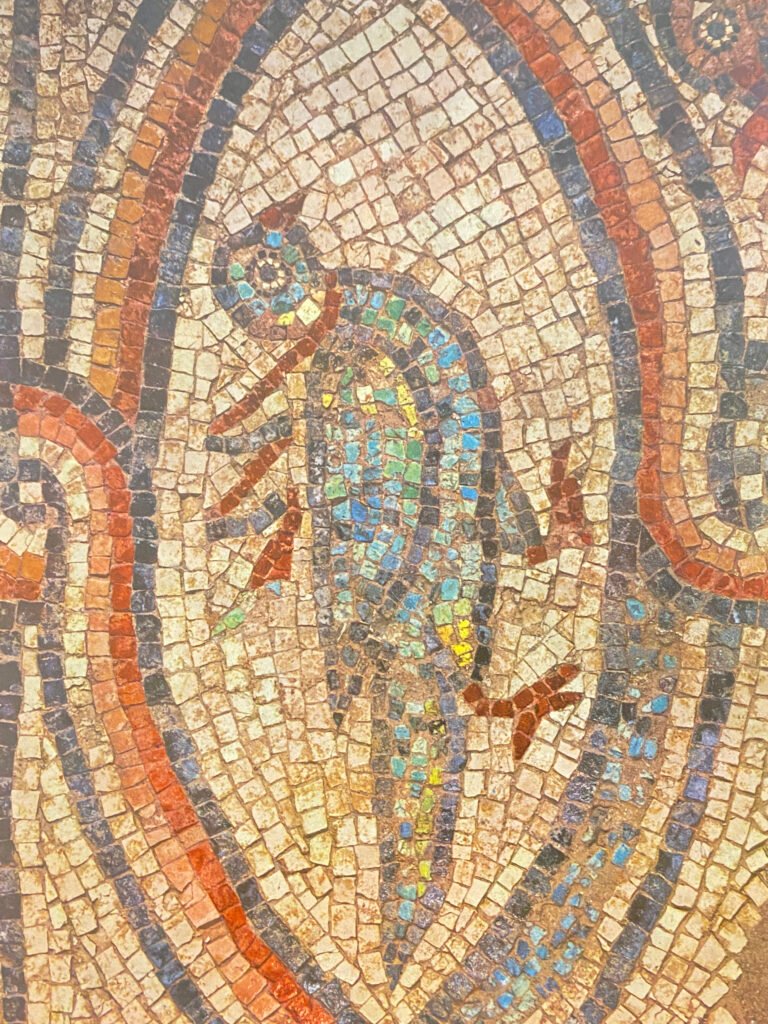

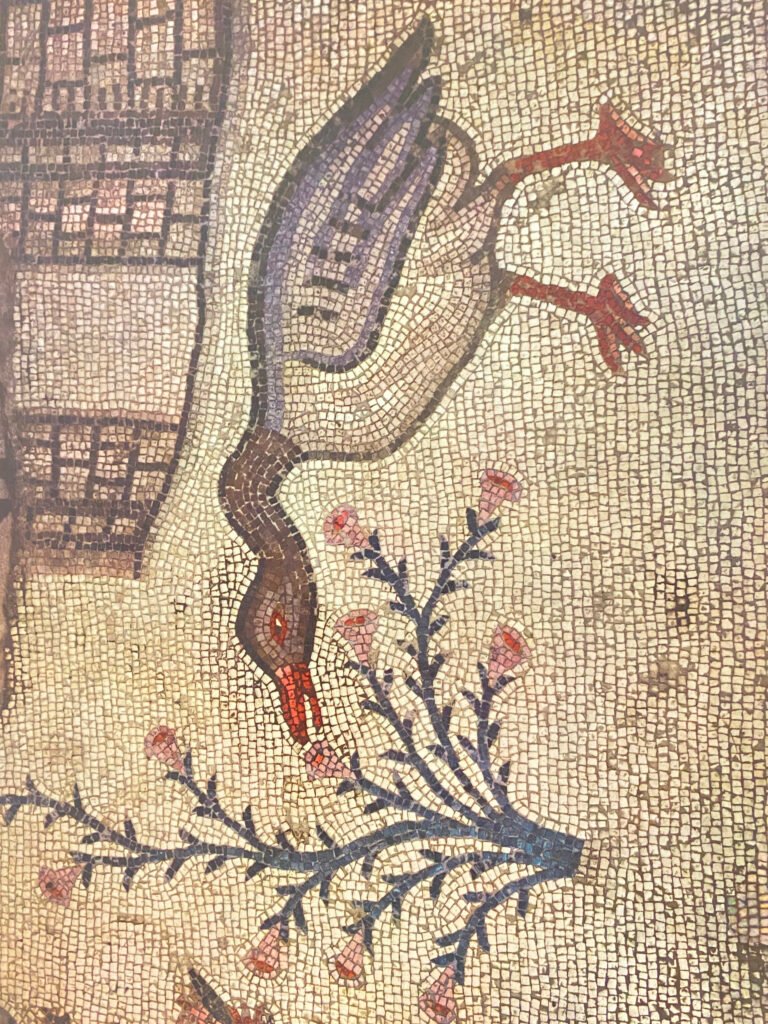

The ancient mosaics discovered in Israel, particularly from the 5th and 6th centuries, offer a fascinating glimpse into the region’s rich artistic heritage. These mosaics, found in synagogues and churches, represent a unique blend of Greco-Roman, Jewish, and Christian traditions, illustrating the cultural convergence that characterized late antiquity.

These mosaics are distinguished by their “strewed” style, where elements appear randomly arranged, evoking the naturalism of wildflowers in a meadow.

This approach marked a significant departure from the rigid, linear designs typical of earlier Oriental art. Instead, the mosaics adopt a Greco-Roman aesthetic, focusing on realism and the dynamic representation of life. The artists’ innovation is evident in their ability to combine symbolic and naturalistic elements, creating compositions that resonate with a sense of freedom and vitality.

One mosaic, with inscriptions written in Hebrew, can be found at the Severus Synagogue in Hamat Tiberias, located in northern Israel. This fourth-century mosaic features Hebrew inscriptions alongside depictions of Jewish symbols, such as a menorah and a tabernacle, as well as a zodiac with the Greek sun god Helios, reflecting the cultural interplay of the time.

Another notable example, located in the contentious West Bank, is the mosaic found in the Shalom Al Yisrael Synagogue in Jericho. This ancient synagogue dates back to the 6th or 7th century CE and features a well-preserved mosaic floor. The mosaic includes Hebrew inscriptions, such as the phrase “Shalom al Yisrael” (“Peace upon Israel”), which gives the synagogue its name.

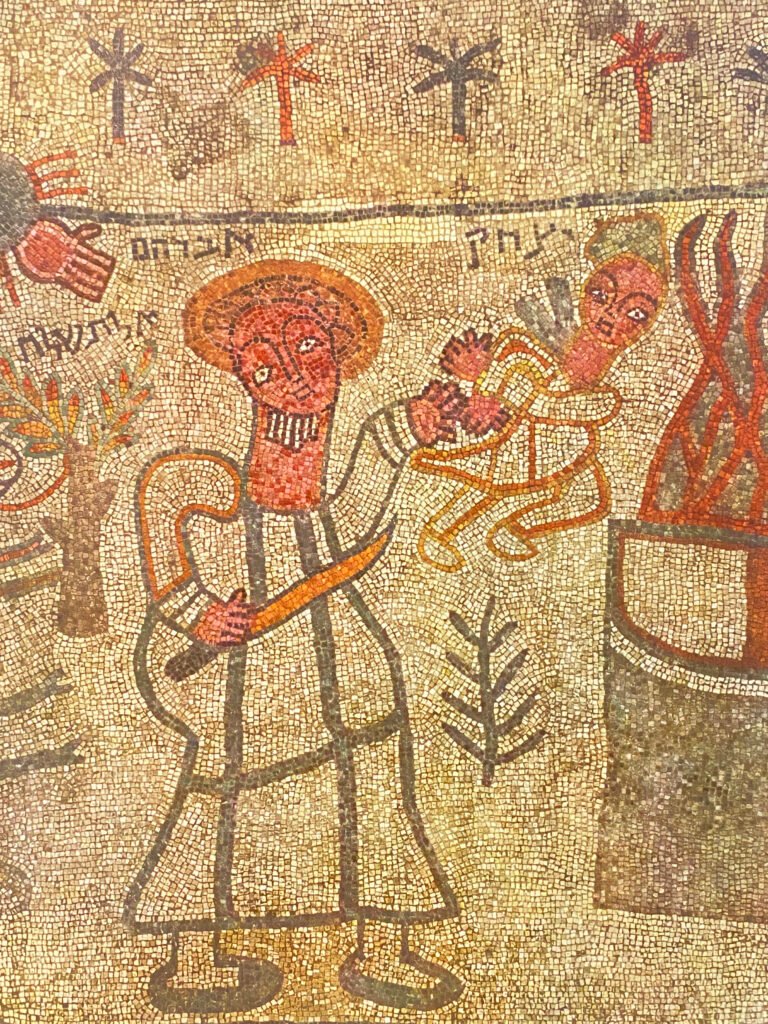

Among the most celebrated of these mosaics is the pavement of the Beth-Alpha synagogue. This mosaic stands out for its originality and depth of religious symbolism. It features scenes from biblical narratives, such as the Sacrifice of Isaac, alongside motifs like the Ark of the Covenant, the zodiac, and the seasons. These elements reflect a distinctly Jewish interpretation of broader artistic traditions, illustrating how local cultures adapted and transformed influences from the wider Mediterranean world.

Technically, the mosaics are remarkable for their use of color, texture, and light. The artists employed techniques that allowed for a rich interplay of light and shadow, enhancing the three-dimensional effect of the scenes. Simple geometric patterns were used to create a sophisticated artistic effect, demonstrating a high level of skill despite the provincial origins of these works.

These mosaics are not merely decorative; they are profound expressions of the cultural and religious life of their time. They show how local artists in Israel adapted and evolved classical art forms to create something uniquely their own. The mosaics of Israel stand as a testament to the region’s role as a crossroads of civilizations, where diverse influences came together to produce art of enduring significance.